- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

A week before Emma Amos: Color Odyssey was set to close and four days before Derek Chauvin’s guilty verdict for the murder of George Floyd, I invited my sister and niece to accompany me to Emma Amos’s retrospective at the Georgia Museum of Art, the first of three sites for the traveling exhibition. As we made the hour drive from Atlanta to Athens, news reports of Black bodies being killed by police lingered in the car, like unwelcome chaperones. Along with the current backlash against teaching the systemic racism that is the warp thread of the United States, these events amplified the timeliness of Amos’s retrospective. Witnessing the breadth of the artist’s career felt momentous in ways that it does not for artists who historically “fit” within the canon. Her distinct orchestration of various media, coupled with her unflagging critique of race and gender, captivate and propel the viewer through the retrospective. And, despite the weight of the subject matter, Amos’s work was ultimately a balm, ushering and uplifting the three of us on our visit.

Color Odyssey celebrates the inimitable career of Amos (1937–2020), highlighting her exploration of printmaking, weaving, painting, and photography and her use of these media to challenge discourses of history, race, and gender. Born in Atlanta, Amos began attending art classes when she was eleven at Morris Brown College. Although she left the South to complete her bachelor’s degree at Antioch College and only returned to Atlanta for a brief time before moving to New York, the nostalgia for her birthplace remained strong throughout her life (Tyler Green, “Emma Amos, Marie Watt,” Modern Art Notes Podcast, January 28, 2021). In the span of her career, Amos worked as a textile designer and weaver, an illustrator for Sesame Street Magazine, and cohost of Show of Hands, an educational craft show for television, and was a tenured professor at Rutgers University. In 1964 Amos became the only female member of the Black artist group Spiral and in the 1980s was a member of several feminist groups, including the journal M/E/A/N/I/N/G and the artist-activist Guerrilla Girls. In addition to her being a mother, each of these experiences informed Amos’s unconventional, boundary-defying studio practice.

Amos is primarily known for her textile paintings, which evolved during the latter half of her career, and her etchings and silk collagraphs, the latter a method she developed in collaboration with printer Kathy Caraccio. The artist’s willingness—or, perhaps more accurately, need—to experiment and push the limits of her media, I would argue, was rooted in her studies as a printmaker. Amos spoke of her penchant for collage and how moving pieces and parts around was integral to her practice (52). Some forms of printmaking are essentially collage: planning demands that the maker break down and determine the placement of the various parts and layers beforehand. For many, this rigidness makes the printing process daunting, but it can also allow for numerous possibilities and a chance for play. This sense of play is pervasive in the exhibition Color Odyssey, along with fearlessness and uninhibitedness.

3 Ladies (1970) is one example of a work that exemplifies Amos’s confidence in the print medium. The image appears very straightforward, which could easily be attributed to Amos’s deftness with the medium. However, the process is more complicated than meets the eye. A combination of etching, relief, and screenprint, the work is a composite of five sheets of paper and measures just over five feet tall. Three figures occupy the composition, but each largely remains in her own space. Amos created this separation by varying the background color and shape around each figure, with just a hint of a shared space between the two women in the “foreground.” In contrast to the woman in the background, who is uniformly a flat white—as is her prop, a chair—a variety of colors, including the cross-hatched texture that creates dimensionality in the woman at right, constitute the other two women’s skin tones. Relatedly, in the earlier painting Godzilla (1966), Amos attended to the figures, three again, in a similar manner. Here, two of the women are composed of a variety of browns, yellows, and greens. They appear more fully present than the central woman, whose pale head, shoulders, and arms are defined partly by the bodily contours and presence of the two figures on either side of her. In both Godzilla and 3 Ladies, whiteness thus functions as an absence, at once secondary and central to the other two figures “of color.” In this manner, Amos analogized the complexities of racial constructs through her technical emphasis on collage—both are layered processes of construction and deconstruction, always in flux and always dependent on proximal relations.

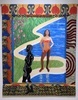

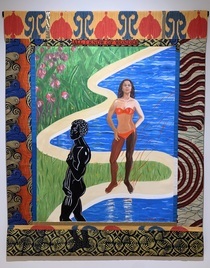

Several of the works in the exhibition demonstrate Amos’s posture on the fluidity of race. Seated Figure and Nude (1966) and All I Know of Wonder (2008) are two examples that readily reveal her position. In All I Know of Wonder, a figure standing in contrapposto wearing a red bikini, presumably Amos, is painted in different skin tones, from shades of “white” to a darker brown; she is the counterbalance to a Greco-Roman sculpture standing in the foreground. Her defiant stance, chin up and hand on hip, refuses to be classified by race or gender. She seems to say: I will define my own identity, create my own wonder, be my own superhero breaking the tenets of classical beauty. In Amos’s words:

In the mid-eighties I noticed that curators from public institutions mostly chose to exhibit paintings of mine showing figures that could be identified as “black.” This pattern made me more determined to use a multicolored mix of skin tones. Every African-American artist, including those whose work is more abstract or who do not paint recognizably “black” figures, has confronted curatorial and editorial definitions of “black art” that both include and exclude works, thus continuing the segregation of images and artists. (34)

In addition to printmaking, photography was a medium Amos incorporated into her work, using its ostensible claims to truth to confront myths of race and gender. In two works, Mississippi Wagon, 1937 (1992) and Equals (1992), she incorporated the same black-and-white photograph, inherited from a relative, depicting two Black men, one standing, the other sitting on a horse-drawn wagon stopped in front of a house and field. In Mississippi Wagon, 1937, the photograph is centered against a loosely painted Confederate flag. The flag is a framing device, but it is also interrupted by the photograph it borders. This iconoclastic arrangement is one of many examples of Amos’s ability to use simple but charged gestures to counteract contested narratives. In Equals the photograph replaces the canton of the US flag, becoming one element in another elusive story embedded in the history of a national icon. As Phoebe Wolfskill writes in the catalog, “Amos’s rupture and dislocation of the photograph and flag unsettles any assumed meanings each may hold . . . we cannot view these human beings without the structure surrounding them, and we cannot view the Confederate flag without considering the actual Black people imperiled by its racist logic” (64).

Color Odyssey highlights the unique aspects of Amos’s career and her courageous and unapologetic approach to her work. Her capacity to address issues of race and gender through a consistently innovative lens is remarkable. Perhaps most important is the pervasive framework of sincerity in her work. Although she tackled grand narratives of racial identity in the United States, Amos’s confidence in highlighting her individual experiences as a Black, female artist makes the work extraordinary. For example, both her Water and Falling series evolved out of personal anxieties and fears, including her inability to swim. However, the artist’s unconventional use of textiles introduces a whimsical note into these works that transports the viewer to a place of euphoria rather than unease. Amos’s use of textiles denies any prescribed hierarchy to which the medium may belong. She challenged craft and gender bias and unabashedly integrated weaving with her paintings. Catalog contributor Lisa Farrington writes, “Amos’s decision to obfuscate this high/low art divide by consolidating the so-called ‘fine art’ of painting with the ‘artistry’ of textile making was nothing short of alchemy” (44). This self-assuredness and honesty are also evident in Amos’s series of runners and athletes, which are unexpected in the best of ways. In each of these works, the artist allows the natural characteristics of the textiles, fraying and unraveling, to do the work for her.

The exhibition catalog includes in-depth essays covering Amos’s unique approach to her selected media. Farrington details her use of textiles, Laurel Garber discusses her approach to printmaking, and Wolfskill pinpoints Amos’s use of photography. My only criticism of the physical exhibition concerned the decision to paint the gallery walls in the latter half of the show—which consisted mainly of Amos’s textile works—a separate color. This created a division between her earlier works informed by Pop art and Abstract Expressionism and her later integration of textiles into her paintings. This results in a hierarchy that could be interpreted as high art versus low craft, a distinction that Amos actively and successfully rejected in her life and her work.

Krista Clark

Assistant Professor, Division of Creative and Performing Arts, Morehouse College