- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

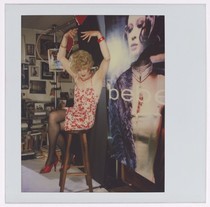

In 2017, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art received a trove of 9,200 Polaroids taken by unknown artist April Dawn Alison (1941–2008). To use curator Erin O’Toole’s words, Alison was “the private feminine persona” of Alan Schaefer, a reclusive Oakland-based commercial photographer with a proclivity for short dresses, high heels, wigs, and jewelry, whose gender identity was known only to a few relatives and friends. The voluminous archive consists mostly of self-portraits taken in the artist’s two-bedroom apartment over the course of four decades. The photographs were discovered by artist Andrew Masullo, who purchased the archive from the liquidator and two years later donated it to the museum, which, in the summer of 2019, exhibited the photographs in public for the first time. The exhibition, organized by O’Toole, was accompanied by a catalog (also edited by O’Toole) with contributions by writer Hilton Als and artist Zackary Drucker. The show featured a selection of about three hundred mostly unlabeled color Polaroids grouped into clusters of serial studies, which demonstrated the photographer’s technical prowess, systematic approach, precision, and ingenuity. The exhibition showcased the diversity of Alison’s extensive inventory of female archetypes inspired by representations of women in film, advertising, and pornography, varying from domestic respectability to hardcore BDSM imagery.

The museum’s decision to posthumously display these private images in public—possibly against the artist’s will—is, O’Toole believes, morally justifiable since they can “enrich the conversation around solidarity and difference at a time of both increased visibility for and increased hostility toward those with non-normative gender identities.” Furthermore, the show follows in the footsteps of recent exhibitions dedicated to queer and transgender visibility, such as the Barbican’s Another Kind of Life: Photography on the Margins (London, 2018), Art Gallery of Ontario’s Outsiders: American Photography and Film, 1950s–1980s (Toronto, 2016), and Cindy Sherman’s Other People’s Photographs (City Gallery Wellington, 2016–17), which featured selected items from the artist’s archive of found albums, including a collection of snapshots taken at “Casa Susanna,” a resort in the Catskills, New York, that catered to a group of transvestite men during the 1960s. These exhibitions tapped into a contemporary fascination with the vernacular—and a newly found interest in found photography—cultivated by art institutions, collectors, and scholars. The prevalence of snapshots and family albums in major museums is a case in point, signaling the historical importance of these heretofore understudied genres. Geoffrey Batchen argues that “vernacular photography is the absent presence that determines its medium’s historical and physical identity. . . . Truly to understand photography and its history . . . one must closely attend to what that history has chosen to repress” (Each Wild Idea: Writing, Photography, History, MIT Press, 2002; 59). The repression of the vernacular coincides with the marginalization of gender and sexual subcultures, and the call to recount their histories has been adopted by curators and museums worldwide.

The essays featured in the April Dawn Alison catalog address a major problem concerning what Als calls “the silence surrounding [Alison’s] pictures” (n.p.)—that is, the discrepancy between the photograph’s muteness and the visual certitude of the photographic indexical mark (with its evidentiary promise). The paradox of what Henry Fox Talbot dubbed photography’s “mute testament” is intrinsic to the medium and has been an ongoing concern for scholars and practitioners since its inception. Alison’s photographic archive is a case in point: its rich visual material never congeals into “biographical facts” (Als). And so, many questions remain unanswered. O’Toole, for example, ponders the artist’s gender identification; Drucker wonders who Alison imagined “savoring” her images. Accepting that the answers cannot be extricated from the pictures, the three writers devise various strategies to counter photography’s factual recalcitrance. In an attempt to make the mute speak, they perform ventriloquist acts and stage conversations that fictionalize their interlocuter’s absent voice.

The first essay, written by O’Toole, opens with a striking epigraph taken from a text entitled “Bobbie goes private,” originally published in the magazine Transvestia in 1963. Transvestia was founded in 1960 by Virginia Prince, known today as a pioneering advocate for the North American transgender community. Prince envisioned Transvestia as an outlet for a community of heterosexually oriented transvestite men (a term she used to define the group’s gender identity) who, according to the magazine’s credo, sought to express, learn about, and embrace the feminine aspect of their personality. In her Transvestia essay, Bobbie recounts the exhilaration she felt when she spent time with another self-identified transvestite named Susanna Valenti, owner of “Casa Susanna.” The passage that O’Toole reproduces goes as follows: “Susanna paid me the nicest compliment about my expression of the inner self. She felt that . . . [as a woman I seemed to] come alive with a sparkle in my eyes and a vivacity that truly expressed the being within. . . . I can sum it up by saying: ‘As a man I exist, as a woman I live.’” The last sentence is so illuminating that historian Robert Hill used it for the title of his PhD dissertation exploring the discourse around heterosexual transvestism (University of Michigan, 2007). Whereas O’Toole never explicitly engages with the epigraph’s idiosyncratic contents and historical figures, Drucker argues that Alison’s gender identity exemplifies “the category of ‘transvestite’” prevalent in the 1960s and 1970s. Though Alison’s familiarity with Transvestia is only hypothetical, Drucker rightfully situates her putative gender expression within that specific historical framework, marking Virginia Prince, Susanna Valenti, and Transvestia as significant historical landmarks.

In the second essay, Als addresses the silence of the photographs by arguing that they “are a record of a double consciousness,” thereby imagining Schaefer/Alison’s inner dialogue featuring “the he who wants to be a she and the she who is a model and photographer.” Admittedly unable to determine the “facts” concerning the artist’s gender identity, Als weaves this uncertainty into the fabric of his prose, accentuating the linguistic implications of Alison’s gender indeterminacy. “Who took the pictures? Him or her?” he muses, concluding that it must be “both of them.” However, this reading is disturbingly fixated on the presumed primacy of a biological fact: “After all,” Als maintains, “April was born a man.” This insistence consecrates biology as critical to the formation of a trans person’s psyche, echoing a medical discourse that essentializes transgenderism. At certain junctures, Als’s words read as borderline derisive: “Putting on those shoes and wigs . . . allowed our guy becoming a woman to expose his soul to himself.” Yet, Als’s embrace of the language of gender binarism is countered by O’Toole’s and Drucker’s historically grounded arguments, which decisively conclude that it is “most appropriate here to refer to the maker and the subject of the portraits in this book as ‘she’” (O’Toole).

Drucker’s final essay, written in great solidarity with Alison, is the most historically specific. Unlike Als, Drucker doesn’t subscribe to gender determinism nor to the binary linguistic prism through which the photographs are construed along strictly gender categories. Drucker emphasizes that the photographs devise a stage wherein “a singular body represents divergent selves—creator and object, dominator and subjugate.” A profound statement concerning the performative nature of the medium, Drucker’s argument contests the reduction of Alison’s artistic utterances into gender idioms. The photographs do not merely demonstrate the “split” endemic to gender binarism, but rather show that the self consists of a plethora of images. Drucker rightfully follows the other writers by situating Alison within a long tradition of artists who used photography to construct nonconforming gender identities. O’Toole, for instance, underscores the photographer’s artistic “ambition,” pointing out that one of the fourteen boxes storing the archive had a small label reading “April Dawn Avedon” affixed to it. She ponders whether Alison was aware of Cindy Sherman’s work or Andy Warhol’s self-portraits in drag, whereas Als brings up Diane Arbus’s pictures of drag queens. Drucker traces a more detailed visual history of gender nonconformity, showing that the history of photography has been permeated by such imagery, from Julian Eltinge’s 1890s female impersonations, to Man Ray’s documentation of Barbette and Marcel Duchamp’s alter ego Rrose Sélavy, to Weegee’s, Brassaï’s, and Arbus’s documentations of queer subcultures. By underlining the pervasiveness of these images, Drucker challenges the assertion that Alison was “ever truly alone.”

The catalog and exhibition succeed in showing the centrality of the photographic act to Alison’s visual universe, underscoring her experiments with the medium’s capacity to transform reality by fictionalizing its appearances and thereupon documenting them. Alison fashions scenes of an artist at work, adjusting her cameras and setting up a tripod. Often she is portrayed in the midst of taking a picture; others show her completely absorbed in the act of scrutinizing her self-portraits, products of her own labor. Photographs, Alison makes clear, are touchable, affectively invested objects. By the same token, let us notice the photographic reproductions that proliferate in the domestic spaces in which she stages her performances: the heavily decorated living room, replete with pictures of actresses and celebrities; the crowded images-saturated kitchen, well stocked with pictures, magazines, and books; and the small studio spaces, where she sets up elaborate photoshoots, posing, for instance, in front of numerous “bebe” advertising posters, mimicking the editorial photographs’ hypersexualized visual language. One wonders if Alison, in her capacity as a commercial photographer, is the person who shot the original ads, though one can only surmise. But the photographs bear witness to another kind of truth that transcends factual details: the truth of April Dawn Alison’s art of photography.

Ron E. Reichman

Doctoral Student, Department of Art & Art History, Stanford University